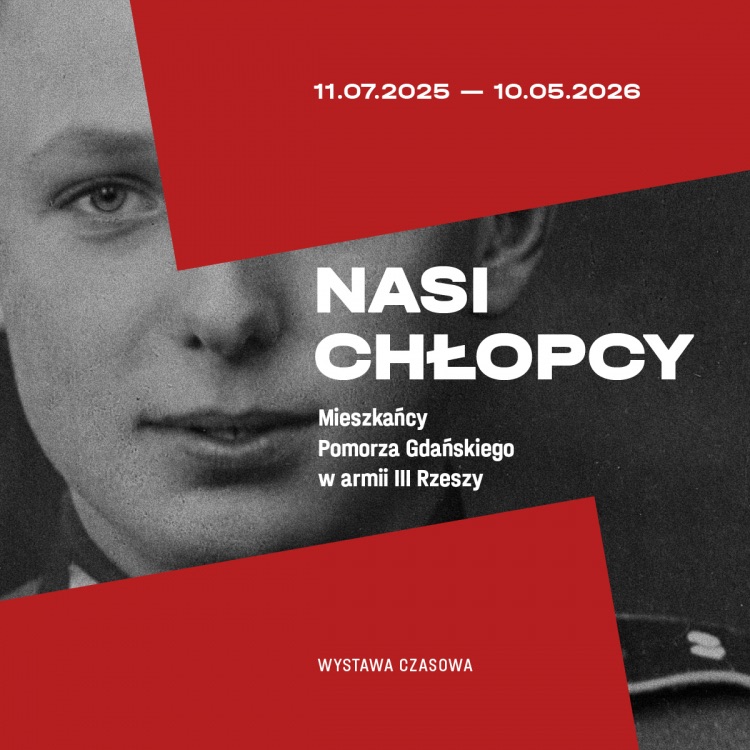

Gdańsk, lipiec 2025. W sercu Wolnego Miasta, gdzie rozpoczęła się jedna z najtragiczniejszych kart w historii Polski, otwarto wystawę zatytułowaną „Nasi chłopcy. Mieszkańcy Pomorza Gdańskiego w armii III Rzeszy”.

Jej organizatorami są trzy renomowane instytucje: Muzeum Gdańska, Muzeum II Wojny Światowej w Gdańsku oraz Centrum Badań Historycznych PAN w Berlinie. I choć – jak zapewniają twórcy – wystawa nie ma oceniać, lecz „tłumaczyć złożoność losów mieszkańców Pomorza”, jej tytuł oraz sposób narracji stawiają fundamentalne pytania o polską rację stanu, politykę historyczną oraz o to, kto dziś pisze historię Polski.

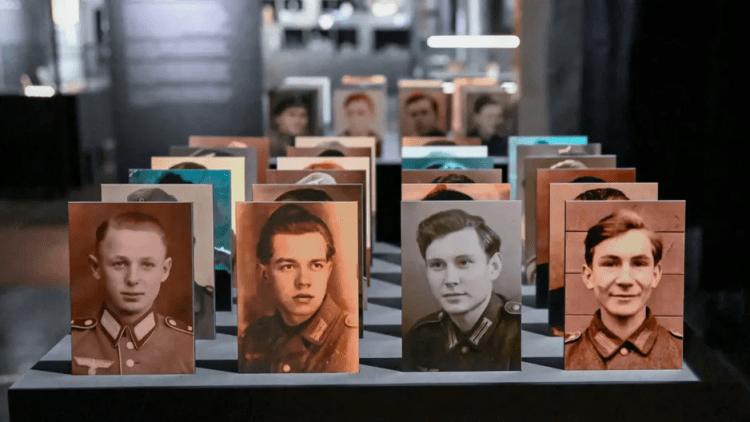

Wystawa “Nasi chłopcy” w Muzeum Gdańska. Fot. Muzeum Gdańska

Pamięć jako pole bitwy

W czasach, gdy wojna toczy się nie tylko na frontach, lecz również w przestrzeni symbolicznej, język ma znaczenie strategiczne. Tytuł wystawy – „Nasi chłopcy” – to nie tylko kontrowersyjna fraza. To celowy zabieg komunikacyjny, który rozmywa granice między ofiarą a sprawcą, pomiędzy państwowością polską a machiną ludobójstwa III Rzeszy. To język, który ma wzbudzić emocjonalną identyfikację z ludźmi, którzy – niezależnie od okoliczności wcielenia – nosili mundur Wehrmachtu, armii odpowiedzialnej za zbrodnie wojenne i Holokaust.

W takim ujęciu historycznym Polska przestaje być jednoznaczną ofiarą niemieckiej agresji, a staje się częścią „wspólnej europejskiej tragedii”, gdzie wszyscy byli wplątani, wszyscy jakoś cierpieli – i wszyscy są w pewnym sensie winni. Takie ujęcie to wprost naruszenie polskiej racji stanu.

Trudna historia? Tak. Fałszywa symetria? Nie.

Nie ulega wątpliwości, że historia Pomorza Gdańskiego – regionu, który po 1939 roku znalazł się w granicach III Rzeszy – była tragiczna. Wielu mieszkańców zostało przymusowo wcielonych do Wehrmachtu, co jest udokumentowanym faktem historycznym. Ale czym innym jest badanie tragicznych wyborów ludności cywilnej pod okupacją, a czym innym tworzenie języka, który zaciera moralną różnicę między Westerplatte a Stalingradem, między Powstaniem Warszawskim a ofensywą Wehrmachtu na Wschodzie.

Trzeba jasno powiedzieć: żołnierze Wehrmachtu nie byli „naszymi chłopcami”.

Nasi chłopcy ginęli w Katyniu, walczyli pod Monte Cassino, umierali na barykadach Warszawy i znikali w czeluściach niemieckich i sowieckich obozów. To ich mundury, ich wartości, ich przysięga na wierność Rzeczypospolitej stanowią fundament polskiej tożsamości i niepodległości.

Niemiecka polityka historyczna w Polsce – czy na własne życzenie?

Należy zwrócić uwagę na szerszy kontekst wystawy: od lat trwa proces tworzenia „wspólnej pamięci europejskiej”, którego celem jest złagodzenie winy Niemiec poprzez tworzenie narracji o „wielu współodpowiedzialnych narodach”.

W tym kontekście projekty takie jak „Nasi chłopcy” nie są przypadkiem, ale częścią strategii: przesunąć punkt ciężkości z win Niemiec na „tragiczne uwikłania” narodów okupowanych. A skoro Pomorzanie służyli w Wehrmachcie – to może reparacje nie są potrzebne? Może nie było jednej strony zła?

W tym kontekście finansowanie takich projektów przez polskie instytucje z publicznych środków budzi ogromne wątpliwości.

Bo czy można sobie wyobrazić, by w Niemczech powstała wystawa pod tytułem „Nasi chłopcy. Żydzi w Sonderkommando”? Oczywiście nie – tam szanuje się granice moralne i symboliczne. W Polsce te granice – jak widać – coraz częściej są przekraczane własnymi rękami.

Polska racja stanu: granica musi zostać wytyczona

Polska racja stanu w zakresie pamięci historycznej polega na:

- Jasnym określeniu roli Polski jako ofiary II wojny światowej.

- Obronie tożsamości narodowej przed relatywizacją historii.

- Odrzuceniu narracji, które wpisują się w interesy innych państw kosztem prawdy historycznej.

Jeśli dziś nie powiemy „stop”, jutro możemy obudzić się w rzeczywistości, gdzie polskie ofiary są równoważone niemieckimi oprawcami, a pojęcia zdrady i służby Polsce stają się rozmytymi kategoriami.

Polska ma prawo, a wręcz obowiązek, oczekiwać od swoich instytucji publicznych odpowiedzialności za przekaz historyczny. Nie chodzi o cenzurę, lecz o to, by:

- słowa dobierać z rozwagą – bo słowa budują narracje, a narracje budują przyszłość,

- odróżniać badania naukowe od przekazu społecznego,

- bronić historii ofiary – bo taka była Polska – z godnością, ale bez kompleksów.

Wystawa „Nasi chłopcy” mogła być ważnym głosem o tragedii Pomorzan wcielanych do niemieckiej armii. Ale przez zły język, zły tytuł i brak zrozumienia kontekstu – stała się symbolem czegoś znacznie groźniejszego: redefinicji pamięci historycznej w duchu narracji niemieckiej.

A to jest coś, na co Polska – jeśli chce pozostać państwem suwerennym nie tylko politycznie, ale i symbolicznie – nie może sobie pozwolić.

Autorka: Iwona Golińska, prezes Polish Sue Association in Great Britain

En.

“Our Boys” in Wehrmacht Uniforms? About an Exhibition That Attacks Polish National Interests

Gdańsk, July 2025 — In the heart of the Free City, where one of the most tragic chapters in Polish history began, an exhibition entitled “Our Boys. Residents of Gdańsk Pomerania in the Army of the Third Reich” has opened.

It is organized by three renowned institutions: the Gdańsk Museum, the Museum of the Second World War in Gdańsk, and the Polish Academy of Sciences’ Centre for Historical Research in Berlin.

Although – as the creators assure us – the exhibition is not meant to judge but rather to “explain the complex fate of the inhabitants of Pomerania,” its title and narrative style raise fundamental questions about Polish national interests, historical policy, and who writes Polish history today.

Memory as a Battlefield

In times when war is waged not only on the frontlines but also in symbolic spaces, language has strategic significance.

The exhibition’s title – “Our Boys” – is not just a controversial phrase. This is a deliberate communication technique that blurs the lines between victim and perpetrator, between Polish statehood and the Third Reich’s genocidal machine.

This language is intended to evoke emotional identification with the people who – regardless of the circumstances of their incorporation- worn the uniform of the Wehrmacht, the army responsible for war crimes and the Holocaust.

In this historical framework, Poland ceases to be an unequivocal victim of German aggression and becomes part of a “common European tragedy,” where everyone was implicated, everyone suffered in some way—and everyone is, in some sense, guilty.

Such a framework directly violates the Polish raison d’état.

A difficult history? Yes. A false symmetry? No.

There is no doubt that the history of Gdańsk Pomerania—a region that became part of the Third Reich after 1939—was tragic.

Many residents were forcibly conscripted into the Wehrmacht, a documented historical fact. But it’s one thing to examine the tragic choices of civilians under occupation, and quite another to create a language that blurs the moral distinction between Westerplatte and Stalingrad, between the Warsaw Uprising and the Wehrmacht offensive in the East.

It must be made clear: Wehrmacht soldiers were not “our boys.”

Our boys died in Katyn, fought at Monte Cassino, perished on the barricades of Warsaw, and disappeared into the depths of German and Soviet camps.

It is their uniforms, their values, their oath of allegiance to the Republic of Poland that constitute the foundation of Polish identity and independence.

German historical policy in Poland – is it self-inflicted?

It is important to note the broader context of the exhibition: the process of creating a “common European memory” has been underway for years, the aim of which is to mitigate Germany’s guilt by creating a narrative of “many nations sharing responsibility.”

In this context, projects like “Our Boys” are not a coincidence, but part of a strategy: to shift the focus from Germany’s guilt to the “tragic entanglements” of the occupied nations.

And since Pomeranians served in the Wehrmacht, perhaps reparations are unnecessary?

Perhaps there wasn’t one side to the evil?

In this context, the public funding of such projects by Polish institutions raises serious doubts.

Can one imagine an exhibition titled “Our Boys: Jews in the Sonderkommando” being created in Germany? Of course not – moral and symbolic boundaries are respected there.

In Poland, as we can see, these boundaries are increasingly being crossed by hand.

Polish raison d’état:

The line must be drawn Poland’s raison d’état in the field of historical memory consists of:

1. Clearly defining Poland’s role as a victim of World War II.

2. Defending national identity against the relativization of history.

3. Rejecting narratives that align with the interests of other countries at the expense of historical truth.

If we don’t say “stop” today, tomorrow we may wake up to a reality where Polish victims are balanced against German oppressors, and the concepts of betrayal and service to Poland become blurred categories.

Poland has the right, and even the obligation, to expect its public institutions to be accountable for their historical narrative.

This isn’t about censorship, but about:

-choosing words carefully – because words build narratives, and narratives build the future,

-distinguishing academic research from social media,

– defending the history of the victim – because that’s what Poland was – with dignity but without complexes.

The “Our Boys” exhibition could have been an important voice about the tragedy of Pomeranians conscripted into the German army. But due to poor language, a poor title, and a lack of understanding of the context, it has become a symbol of something much more dangerous: a redefinition of historical memory in the spirit of the German narrative.

And this is something Poland—if it wants to remain a sovereign state, not only politically but also symbolically – cannot afford.

Author: Iwona Golińska, president of the Polish Sue Association in Great Britain

Leave a comment